Covid-19 variants: how many are there, why are they created and what their existence means

The fact that a virus that we are still fighting might mutate into a different one is highly concerning. Let’s talk about the Covid-19 variants: How are they created? How many really exist? Could a variant appear evades all the vaccines?

For the past few months, governments and institutions have been informing of the proliferation of new variants of the SARS-CoV-2. This is happening because when a virus replicates itself in another organism or makes copies of itself, it changes. It does this thousands of times a day, the same amount of times as transmissions occurring in people or animals. Because all viruses, including the SARS-CpV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, evolve over time.

Each change is called a mutation because it means an alteration in the virus’ RNA sequence. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), most of the changes that occur have little or no impact on the characteristics of the virus. However, depending on where these alterations are located in its genetic material and on the number of these alterations, it can affect its properties, deriving in variants of the virus. This means that they can become, for example, faster to propagate, or more virulent. To put it in easier terms: every day thousands of mutations occur, but very few of them end up being variants.

How many Covid-19 variants do we know about?

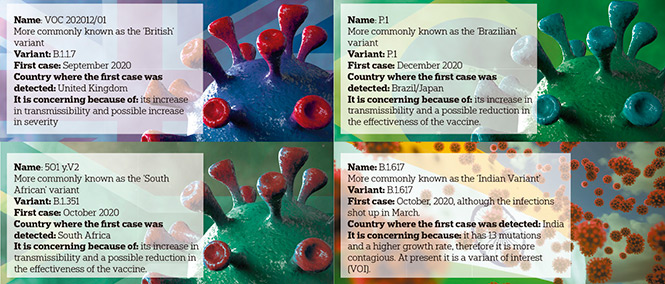

It is one of the most difficult questions to answer as there are – and there will be in the future, numerous variants of the virus. Indeed, in its last report, the Spanish Health Ministry listed at least ten variants that should be monitored. To date, there are three variants that are causing the greatest concern: the British variant; the South African variant and the Brazilian variant, commonly using the names of the places where the first case appeared. Four, if we count the Wuhan variant, which we could consider to be the ‘original’ one (although in turn, it is derived from other variants). This method for referring to the variants will change in the near future. According to the doctor responsible for emerging diseases and zoonotic diseases at the WHO, Maria Van Kerkhove, this organism is working to change the names of the Covid-19 variants. The aim is to remove the link to the place where the person with the pathogen is located and to not stigmatise the countries where the variants are detected for the first time and the people who live there.

January 2020: the beginning

As the WHO underscores, the virus’ mutation potential increases with the frequency of the infections or contagions and this is what happened at the end of January, 2020. A variant of the SARS-CoV-2 appeared with an alteration in its code. The B.1 variant. Just a few months were necessary for it to replace the initial virus detected in Wuhan: in June, 2020 it became the dominant variant throughout the world. In December, the authorities in the United Kingdom informed the WHO of the identification of a new variant of the SARS-CoV-2, called SARS-CoV-2 VUI 202012/01 (due to the initials for Variant under Investigation in English, year 2020, month 12, variant 01). A few days later, South Africa alerted of the detection of a new variant. Three weeks later, Japan and South Korea did the same: they had identified a new variant in several people who had returned from the Brazilian Amazon region. With differences, the three variants share great resistance against the antibodies generated, either due to exposure to Covid-19, or due to vaccination. To different degrees, they share a greater capacity for transmission, which has led them to be categorised by the WHO as ‘Variants of Concern’ (VOC). A category that is above the Variants of Interest (VOI), which are also under surveillance. The difference between them is that there is already evidence of a greater transmissibility of the VOCs, more serious cases of disease (higher amounts of hospital admissions or deaths), lower effectiveness of the treatments or vaccines or problems in diagnosis detection. They need, in short, a more exhaustive monitoring.

Should we be concerned about the change of SARS-CoV-2?

Just over a month ago, a new study published in the magazine Nature warned about the possibility that coronavirus is evolving to ‘escape’ the current vaccines. Is this possible? The nature of the virus pushes it towards survival and this leads it to escape in the opposite direction, but this does not imply that the vaccines stop being effective. It is normal for virus to change. Additionally, the SARS-CoV-2 is evolving more slowly than other known RNA virus’ such as influenza (for which year after year, new vaccines are developed against the new strains) or HIV. For this reason, the scientific community is monitoring hundreds of thousands of sequences of the virus on a huge database called GISAID, in order to closely follow their evolution and mutations, the incidence of their variants and to anticipate any possible necessary modifications in the public health measures or to modify the composition of the vaccines.

Does a virus simply mutate when it replicates itself?

A virus cannot reproduce itself and it needs another host, without which it cannot prosper. The SARS-CoV-2 makes copies of its genome, which contains 30,000 letters, in the cells of an organism. When it does this, sometimes it makes ‘errors’ or mutations. A mutation does not only occur with the replication, but a high number of replications do derive in a greater risk of mutation or error in the replica. This is a statistical fact. In all the mutations that occur, not all of them mean a competitive advantage for the reproduction of the virus. Some can be neutral or even harmful for its reproduction. But when a mutation allows it, for example, to attach itself better to the cell, the resulting version will spread with greater ease than the previous ‘versions’.

Why are some variants more infectious than others?

This is what has happened with the British variant (B.1.1.7), the most common lineage in Europe and also in the USA, according to recent information from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States. It is also the most common variant in Spain. Experts have described it as a variant with faster propagation: according to the WHO, between 36% and 75% more transmissions with respect to previous variants. The key, once again, lies in its genome, the mutation of which has been researched by different study groups. The magazine Science talks about the conclusions reached by the researchers at the Boston Children’s Hospital in the United States, which have verified that the three VOCs have the D624G mutation in common. This alteration causes a change in the structure of the S protein, encouraging the adherence of the virus to the cells (greater entry capacity) and giving it greater contagion speed.

Are the vaccines prepared to inhibit the variants?

According to the WHO, the changes or mutations that are being recorded should not invalidate the effect of the vaccine. As they indicate, in the case of any of these vaccines being less effective, it is possible to change the composition to increase the protection against these variants. However, some studies, such as the one carried out by researchers at the German Primate Center-Leibniz Institute for Primate Research and Jan Münch from the University of Ulm (Germany), point out that the variants are inhibited less effectively. If this happens and the variants were to become less sensitive to the antibodies, the scientific community can adjust or reformulate the composition of the vaccines. In this scenario, the vaccination strategy is essential to prevent more contagions that could derive in new variants that could be resistant to the vaccines.

Does a variant move to a strain?

Not exactly. A strain differs from a variant due to the fact that the strain has a more drastic genetic mutation compared to the initial virus. We are talking about a number of mutations that derive in a substantial change in the virus that would imply, for example, that the vaccine would no longer be effective. This is what happens every year with the new ‘strain’ of ‘flu, which needs a new vaccine.

How can we prevent future new variants?

Stopping the propagation of the virus continues to be fundamental. As more people are vaccinated, the experts expect the circulation of the virus to decrease, which will mean fewer mutations and a reduction in the risk of new variants appearing. A strategy that not only must be supported by the effort made by the governments to speed up the vaccination process, but that also keeps the spotlight on prevention. Frequent hand washing, the use of face masks, physical distancing, good ventilation indoors and avoiding crowded or closed places are essential factors to clip the wings of the virus and sabotage its unavoidable mutations.